A New Tool for the Cupping Kit: The Cafe Imports Coffee Rose Offers a New Model for Sensory Evaluation

By Ian Fretheim

Cupping is one of the most interesting and engaging activities available to specialty coffee professionals. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most gate-kept, poorly defined and, arguably, antiquated activities. Sensory science has come a long way since its inception in the 1940s. Nevertheless, the general approach to cupping in specialty coffee is as if little of that had ever happened and is itself much the same as when it was conceptually introduced in the mid 1980s, and certainly as when it was refined in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Forthcoming updates, for example to the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) system, are certainly needed, and it is my sincere hope that these updates warrant new entries on the cupping form family tree.

While there are real limits to the suitable application of sensory science tools in many of the common use cases associated with assessing specialty coffee, there are also notable shortcomings in the common approach to cupping. The SCA’s recently published Coffee Sensory & Cupping Handbook provides an excellent and concise primer; however, it does not sufficiently prioritize the application of its contents to addressing and advancing the outdated and unreliable components of the current cupping model. In some cases, the current proposals even entrench problematic concepts (e.g., equating distinctive attributes with quality). In other cases, they complicate assessment by adding traditional descriptive and check-all-that-apply, or CATA, components on top of the legacy affective ones (indicating acceptance or preference). Each of these are valid options for the applications that they were designed for, but those applications are notably different.

Independent companies have much more freedom to innovate (I do not envy anyone charged with herding the collective cats of us, the specialty coffee industry) and several have sought to uncover, implement and integrate as far as we could applicable sensory science principles and protocols in our cupping programs, and specifically in the development of new cupping forms.

As an example of this innovative work, Cafe Imports’ newly developed cupping tool—the Coffee Rose—comes after two years of work to build a new suite of tools for coffee assessment. These new tools include a new cupping form, scoring engine, lexicon with assessment value standards, flight building and blinding module, and various reporting features.

Before diving into the specifics of the Coffee Rose, let’s explore some of the challenges inherent in the existing quality measurement tools available to the specialty coffee industry.

The Cafe Imports Coffee Rose is a newly developed tool for coffee assessment, with user experience designed by Devon Barker.

Quality and Standards

Two notable contributing factors to the mismatch between coffee cupping and sensory science are the former’s misapplication of the concept of quality and its lack of supporting valuation standards. Quality is not a measurable coffee attribute; it is a judgment that humans apply to coffee attributes. Think of it like this: A coffee cupper (with the proper training and experience) can tell you if a coffee’s acidity is predominantly citric or malic, and again how intense that acidity is; however, determining the quality of those acids at given intensities or in various contexts is a different order of procedure that requires active value judgment and decision making.

Humans don’t decide how much or what kind of acidity a coffee has. We do decide how we value those things, or how distinctive we think they are when we observe them. It is important to note that such a decision (that of quality or valuation) will always be made somewhere in the assessment process. The issue here is in leaving it to the cupper to decide on the fly, versus the superior alternative of building it into protocols via form design and transparent valuation standards.

The valuation decision registers little difference between the concepts of quality and distinctiveness. Both require but often lack explicit standards that transparently lay out value differences between one attribute and another. Surely we are not proposing that the entire coffee assessment paradigm should default to whoever makes up the most creative words or has the least coffee exposure (where everything novel is distinct). Surely the immediately distinct and, in much of specialty coffee, rarely tasted attributes of Monsooned Malabars and Vietnamese robustas are not intended to rate in parity with boutique and meticulously processed arabicas, nor even with the well-processed examples that have become so common as to already be undervalued in today’s specialty coffee environment. Surely the goal is not to undermine the work for coffee sector equity by defining quality in terms that can be meaningful only when applied with exclusivity and that are inevitably personal in scope.

Surely these are not the case. And yet, here we are. Just as there is no document stating that malic and citric acids are equivalent, better or worse than one another, there is none stating that either is equivalent, more or less distinctive than the other. Ultimately this may be for the best. At the industry leadership level, it is likely more appropriate to introduce ideas, tools, guidelines and guardrails than hard standards. Imposed standards are rarely engaged enthusiastically, are thankless to develop, and have proven impractical to apply across such a broad and decentralized space as specialty coffee, in particular with such highly personal metrics as “good” and “distinctive.”

That being said, guardrails are important and, to the extent that we wish to speak about transparency and equity, are owed to those we buy coffee from on the basis of our assessments. If assessment is to factor into the terms of a transaction, then the terms—and values—of assessment must be defined in advance of that transaction. Importantly, the promotion and use of standards does not require industry-level standardization, nor does the removal of “good” and “bad” from cupping forms remove them from coffee assessment.

The Cafe Imports Coffee Rose

This is an exciting time to be in specialty coffee. While the challenges are well ingrained and the answers are not obvious, we’re seeing more and more participants take a crack at finding a way forward. Our solution, the Cafe Imports Coffee Rose, aims to provide a synthesis between the analysis of sensory science and the experiential interpretation of specialty coffee.

The Coffee Rose is an interactive, dynamic, rich content CATA cupping form paired with a user independent scoring engine. The cupping form is presented in the familiar format of a flavor wheel, which itself functions as the CATA array, where each of the flavors, aromas and tastes displayed are active buttons that can be used to select, combine and endorse applicable coffee descriptors.

The “rich content” component refers to two primary attributes of the Coffee Rose. The first is its tiered structure and the ability to endorse either simple, individual descriptors or to build and endorse more complex descriptor strings. The second is that the Coffee Rose’s endorsement protocol uses an indication for intensity, more along the lines of Cafe Imports’ current Qualitative Descriptive Analysis form. These two components allow us to pack significantly more descriptive punch into our CATA array than would be possible in a static list or table format. The “interactive and dynamic” components refer to the way the Coffee Rose alters its appearance depending on the inputs provided, expanding its active section as well as visually providing reference to the underlying scoring standard, though without compromising the principle separating the assessor from the final valuation process in favor of focusing them on the descriptive. We do this by providing a live indication of connotation—unused descriptors have a neutral color that matches that of their category. When selected, descriptors with a net positive connotation are tinted lighter, while those with a net negative connotation are shaded darker. This tinting and shading stacks back down through any prior descriptor strings to the root category button, which displays the net contribution—positive or negative—that it is making to the overall coffee score (see Figure 5).

Structure

The Cafe Imports Coffee Rose is composed of seven attribute categories, four increasingly descriptive tiers, and an intensity indicator. These combine to create a multi-dimensional, descriptive coffee scoring form that is sensitive not only to the broad qualitative categories that we are accustomed to but also to the degree of specificity noted within each, the specific content of notations, and the quantitative intensity of each impression.

The Coffee Rose is sensitive to:

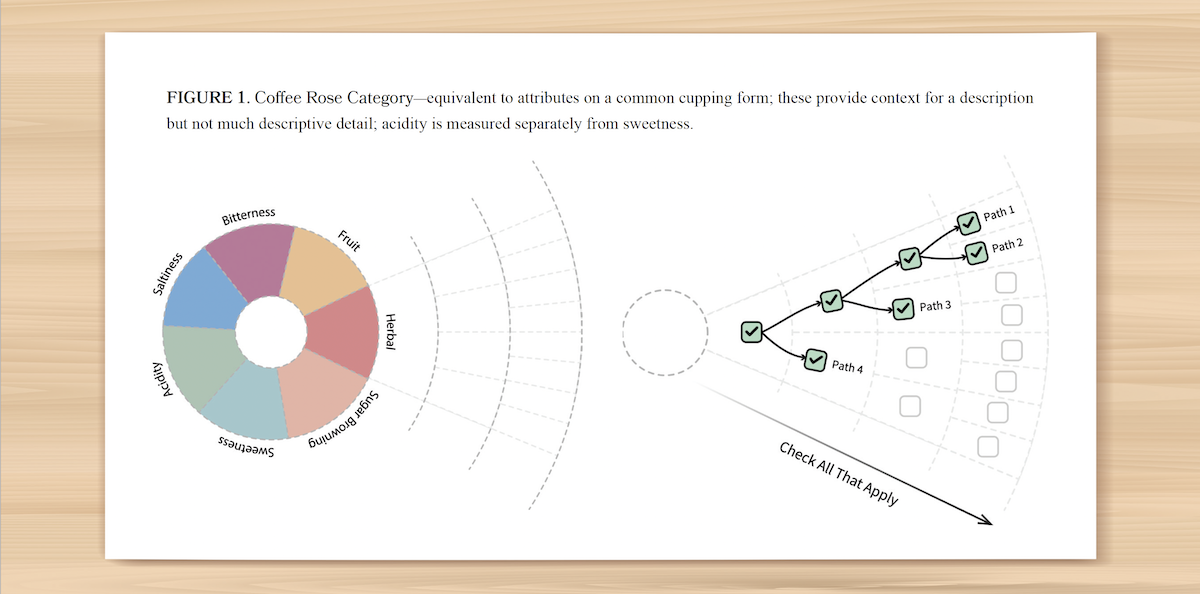

Category: equivalent to attributes on a common cupping form; these provide context for a description but not much descriptive detail; acidity is measured separately from sweetness. (See Figure 1.)

Specificity: how general or specific descriptions are; on common forms specificity is decoupled from scoring; “Specific” tier descriptions have greater descriptive power and value impact than “Qualifier” tier descriptions. (See Figure 2.)

Content: the specific content of descriptors and descriptor strings; on common forms content is decoupled from scoring; apricot has greater value in the Cafe Imports system than coffee cherry. (The difference in value reflects our company’s preference for apricot over coffee cherry. This ensures the descriptors are given equal numeric value for all users, unlike the traditional system.) (See Figure 3.)

Intensity: how intense a descriptor impression is, relative to a reference; common cupping forms tend to be qualitative whereas the Coffee Rose is quantitative; higher intensity descriptors have a greater impact on coffee description and score than lower intensity descriptors. (See Figure 4.)

The Scoring Engine

Driving the Coffee Rose, we have what we call the scoring engine. The scoring engine assigns values to individual entries on the Coffee Rose, calculates values for descriptor strings, sorts and tallies category and then sample-level scores, processes the descriptor strings into natural language forms, and selects from a coffee’s generated descriptor pool for top-level descriptor output.

On a standard cupping form, scores are generated on the basis of values being assigned to attributes by assessors. For example, I might score the flavor of a coffee at 8.5 and then elsewhere on the form describe that flavor as chocolate and raspberry. Someone else might describe the flavor as chocolate and raspberry, but only score it at 7.5. Another person might score the flavor at 8.5 but describe it as savory and floral. Yet another person might score it at 8.5 without offering any description at all.

On the Coffee Rose, attribute scores are generated directly on the basis of descriptive notation and intensity indication. These scores are therefore sensitive both to how attributes are described qualitatively as well as to the quantitative intensities at which those descriptions are observed. While it is still obviously the case that two people can generate different descriptions and arrive at different outcomes for the same coffee, similarity in descriptions reduces differences in scoring when using the Coffee Rose. Further, the differences that do arise between cuppers are made computable by the Coffee Rose and scoring engine, as opposed to when they are individually generated ad hoc. For more information, supporting materials, and a sandbox demo version of the Coffee Rose, please visit cafeimports.com.

Balancing the Precise with the Personal

One of the driving goals for this project was to bring our cupping program into greater alignment with sensory science, but without forcing a round peg into a square hole. For the longest time, I thought that in order to hew closely to the sensory science line I would need to push back against the qualitative, preference and personal language aspects of cupping in favor of emphasizing the quantitative, numeric and measurement components. Indeed, some pushback on this is warranted. As is some finesse.

In the real world of coffee assessment, there is rarely time for the sample sizing and replication common to sensory science studies, which are highly oriented around statistical validation. Further, much of specialty coffee cupping, in practice, boils down to the communication, description and sharing of a human tasting experience that is explicitly not captured by cupping scores.

In many ways, a strict sensory science approach (of the sort that I initially imagined) runs the risk of taking the “specialty” out of specialty coffee, at least for the specialists. Do we want that? By the same token, we have to ask ourselves if we’re okay with the meaning of “specialty” in specialty coffee being anecdotal, imprecise and personal. As much as we may prefer to deny that it is these things, as much as we may want to project rigorous (and dare I say “scientific”) precision and validity, at bottom I suspect that in large part we are not quite willing to let these things go entirely. And beyond shoring up some fundamental issues, I’m not sure that we should be.

There are no “otherworldly beautiful coffees” in the sensory science lab. Nor is there iconoclastic, cynical and delicious rejection of norms. There are just samples with more and less sweetness, more and less acidity, etc. But coffee is clearly personal. From the habitual drinkers who “can’t start the day without my coffee,” even if it’s simply a grocery store ground drip, for whom coffee is already on an equivalent linguistic (and one suspects existential) footing as their very day, to the deep-cut connoisseur who knows more about their morning (and afternoon, and evening) extraction than most of the people involved in getting it to them, coffee is clearly a very personal thing for many. Within the industry, it is the coffee that “I grew” or “I processed” or “I roasted” or “I dialed in and perfected,” or they are the flavors that “I identified” or “I experienced” or “I described.”

The highly personal nature of coffee is a large part of the reason we trade so heavily in anecdotes. It’s our love language and our mother tongue. From my experience, most specialty coffee professionals have at least one go-to anecdote describing their (generally eye opening, if not outright life changing) introduction and entry into specialty coffee, and many have more than one. As for precision, for all of our sifting of coffee grounds and weighing of … everything, at the end of the day most of us still just end up talking about what we like and don’t like, rather than measuring the components of the coffee solution we just took so much care preparing. While lacking in precision, this is deeply personal and often is best expressed through anecdote in an attempt to capture and share (and proselytize and defend) something of the personal novelty not just of the coffee, but of one’s own experience of the coffee, of what the coffee did to them and how it made them feel. Anecdote is the medium of the personal, and that space is naturally imprecise.

We may not want to completely eliminate the personal, anecdotal and imprecise aspects of specialty coffee, but I think that we need to recognize, balance and temper those things with practices that reduce their noisiness and bias, making them more reliable and transparent. In doing so, they can become more descriptive and expressive, supported by the widely recognized foundations of sensory science. As instinctively (and, I think, correctly) as we reject the idea that someone else might dictate to us what is good and what is bad, we must also recognize the untenable position of transacting on the basis of good and bad in a market without compass, let alone standard, for what is good and what is bad. Ultimately, the outputs from our sensory tests should not just be accurate, transparent, reliable, understandable and communicable, they should also foster communication and connection.

***

Ian Fretheim is the director of sensory analysis at Cafe Imports. In 2016, he developed and launched one of the only quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) cupping forms in specialty coffee. In 2018, he obtained the Sensory and Consumer Science certificate from UC Davis and has since focused on developing practical applications from sensory science for the world of specialty coffee.

Advertisement