The Language of Coffee Flavor: A Century of Tasting in Review

By Kat Melheim

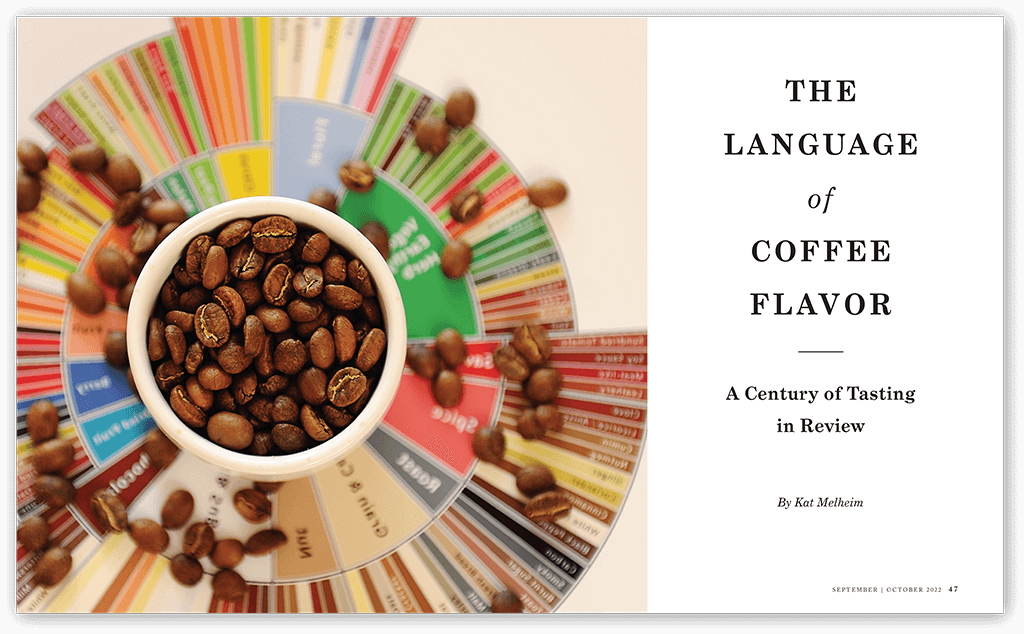

The current iteration of the Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel, now ubiquitous at coffee events and on the walls of cupping labs worldwide, celebrated its sixth anniversary this past June. It was less than 30 years ago, in 1995, that the first edition was released by the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA, now SCA). Before that, there was no visual representation or common language for flavor in the coffee industry. In the grand scheme of a centuries-old coffee trade, we have seen a massive amount of innovation within a relatively short time.

In this article, we explore the history of coffee vocabulary, recent scientific and technological advancements (including the Sensory Lexicon and the Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel), the limitations of the current system and opportunities for future development. So, grab a spoon and come along for the ride as we explore this beautiful, yet sometimes controversial, resource.

Before There Was Flavor, There Was…

In the early days of the global coffee trade (prior to the 19th century), consumers purchased raw coffee and roasted it at home. Coffee was used for its cognitive effects and supposed medicinal benefits, rather than how it tasted. The vocabulary and literature of the time reflect that. In a 1722 book, The Domestick Coffee-Man, English coffee merchant Humphrey Broadbent uses words like sour, flat, distasteful, smooth, pleasant and strong to describe coffee’s flavor. He was primarily instructing people on how to roast and brew coffee in their homes for the best (or least-worst) results, but there wasn’t much nuance. Medical doctor Benjamin Moseley used words like excellent, superior, disagreeable, delicate and exhilarating in his 1792 book A Treatise Concerning the Properties and Effects of Coffee. Again, a slew of adjectives, but no specific flavor notes that tell the reader what the coffee would actually taste like.

By the 20th century, large-scale manufacturers had created a booming global business in coffee roasting. Green coffee was bought and sold in large quantities—generally differentiated only by origin country—and price was based on a coffee’s physical appearance (i.e., bean size, presence of defects or physical damage), rather than specific flavor characteristics. Coffee was being marketed by these roasters as a ground, pre-packaged product, thus buying by taste rather than appearance gave the roaster more quality control over the taste of the finished product.

Advertisement